Ovapedia search :

Title:

Introduction

The lower Otter valley is not well endowed with quality building stone. It has this is common with the whole of the zone lying between the hilly country to the west of the Exe estuary and the M5 corridor, underlain by hard Devonian and Carboniferous rocks on the one hand and the Blackdown Hills capped by the Upper Greensand on the other (Barr, 2007).

Consequently, the stone used for building is a mixture of rather poor quality locally won material and that imported from adjacent areas, supplemented by cob. Exposed stone walls are not a particular house-building tradition of the area perhaps because of this. Most houses are finished in render or stucco and of course, much Nineteenth century and modern housing is made of brick. Consequently, the town- and village-scapes of the lower Otter valley lack the unifying influence of a dominant building stone such as characterises for example Tavistock, Chelston, Sandford and Bishopsteignton in Devon and many towns and villages of the limestone belts in Somerset and Dorset.

The descriptions of building stones and their sources in the following sections are based on fieldwork carried out mainly in 2005 following the method outlined in Barr (2006). It is not an inventory of buildings made of stone (and cob) but a sample of those accessible from the public right of way. Nevertheless, it is believed to provide a reasonably representative snapshot of the nature and distribution of building stone at the time of the survey.

The brief comments on the sources of stone are based more on a study of the available literature than fieldwork and this part of the study requires more work to provide a properly researched idea of where stone used in the Otter valley was won.

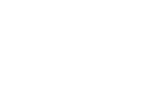

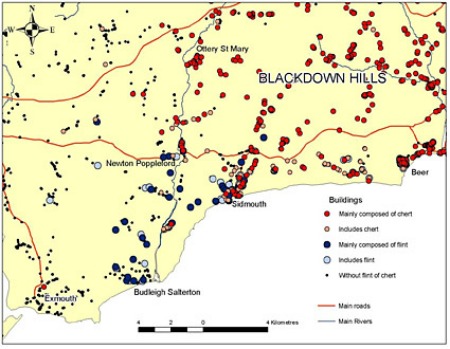

Figure 1. Outline geology of the lower Otter valley

Figure 1 is a sketch of the geology of the lower Otter valley and adjacent areas. The ridge running from Beacon Hill to Peak Hill on the east of the figure is capped by Upper Greensand sandstones, of Cretaceous age, more or less flat lying, and rich in chert nodules and bands, overlain by the Clay with Flints (not shown in the figure), unconsolidated deposits of varying lithology and age extending back to the Eocene (Gallois, 2009). To the east of Sidmouth, the Upper Greensand is overlain by the westernmost outcrop of chalk in England. The materials of the Clay with Flints, including cobbles of flint and chert are derived ultimately from both the Upper Greensand and the Chalk.

The Upper Greensand overlies a sequence of clays, sandstones and conglomerate of Triassic age which underlie the rest of the area of the figure. These rocks dip gently to the east so that the oldest are exposed in the west and successively younger rocks crop out to the east. The Aylesbeare Mudstone Group consists of mudstone and clay, with variable proportions of carbonate minerals and beds of sandstone, and forms the western slopes of the Pebble Bed Heaths (http://www.eastdevon.gov.uk/plg_lct1c.pdf).

The mudstones are overlain by the Budleigh Salterton Pebble Beds Formation, a poorly consolidated conglomerate consisting of well rounded pebbles and cobbles mainly of hard sandstone or quartzite, in a sandy matrix. It forms the core of the Heaths and underlies the higher ground towards the west of the figure. It is overlain in turn by the Otter Sandstone, poorly cemented red sandstone forming the floor of the Otter valley and the rising ground to the west and beautifully exposed in the cliffs to the east of the mouth of the River Otter.

Finally, the Mercia Mudstone Group resting on top of the sandstone, is a second sequence of clays and marls, and underlies the lower slopes of the ridge extending from Beacon Hill to Peak Hill. It is partly obscured by superficial deposits derived from the overlying Upper Greensand and Clay with Flints.

Building Materials

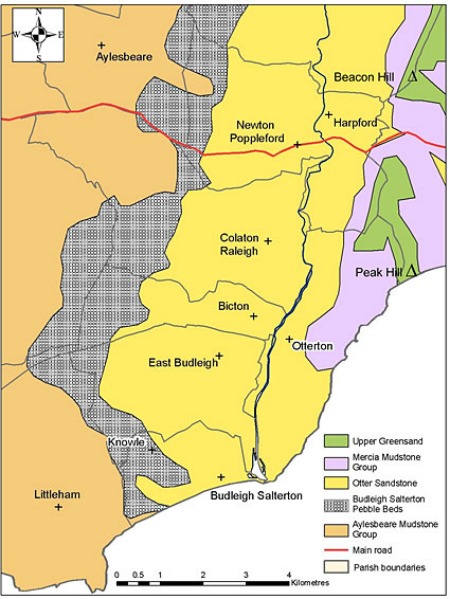

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of the principal building or finishing material of buildings with a stone (or cob) built element included in the survey. As indicated in the introduction, a range of different rock types is used for building with no particular one dominant or characteristic.

Figure 2. Distribution of the main building stones of the lower Otter valley.

Otter Sandstone Formation

This is perhaps the most plentiful stone seen in buildings during the survey of the area with just less than 20 each of houses, outbuildings and elements of churches and about 40 walls and embankments incorporating this material out of a total of 343 buildings in the survey area. Two main rock types are represented;

(i)Red, soft, poorly cemented medium-grained sandstone typically showing bedding defined by grain size and degree of cementation (Figure 3)

(ii)Dark red to blackish mud-flake conglomerate (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Red medium-grained bedded sandstone from the Otter Sandstone Formation. West side of Little Knowle close to junction with West Hill, Budleigh Salterton.

The wall also includes mud flake conglomerate (darker red speckled rock towards the top of the photo), brown sandstone, possibly Salcombe Stone, pale grey limestone from Torbay and rounded cobbles of quartzite from the Budleigh Salterton Pebble Beds.

Figure 4. Mud flake conglomerate from the Otter Sandstone. Tower of St Gregory’s, Harpford.

The sandstone here and elsewhere in East Devon is rather soft and not very durable, so that building blocks tend to have rounded edges and corners. By contrast, in the Vale of Taunton Deane, red Otter Sandstone is an important building stone with much stronger cementation; it is the main building stone of Bishops Lydeard and gives that village its characteristic appearance.

The conglomerate is more durable, perhaps because of more plentiful calcite cement – it was burnt for lime in west Somerset. Its main characteristic is the presence of flakes of mudstone or siltstone, lying in the bedding, and finer-grained and softer than the sandy matrix so that the flakes tend to weather out, giving the surface of the rock a rough pitted appearance (Figure 4).

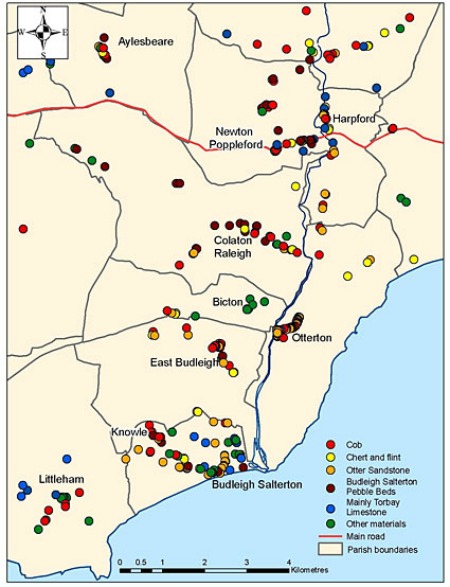

The conglomerate is more plentiful in buildings than the sandstone (Figure 5), the reverse of their relative abundance in outcrop. It is clear that the conglomerate was preferred to the sandstone for building because of its greater durability.

Figure 5. Distribution in buildings of red sandstone and mud flake conglomerate from the Otter Sandstone Formation.

Stone from the Otter Sandstone figures prominently in the buildings of Otterton Mill and Rolle Barton, in the tower of Otterton church and the stacks of cob houses in the main street of Otterton village. The steadings of the farms along the east bank of the Otter between Harpford and Otterton, refurbished or rebuilt by the Rolle estate in the Nineteenth century are characterised by this stone.

The medieval churches of Harpford, Venn Ottery, Newton Popplefpord, Otterton, East Budleigh and Colaton Raleigh (and Aylesbeare) incorporate this kind of stone, usually as the main component of tower, nave, aisles or chancel and in some cases of all of them. Mud flake conglomerate is the main building stone of St Mary’s church, Ottery St Mary, to the north of the area of Figure 2.

Budleigh Salterton Pebble Beds

The Budleigh Salterton Pebble Beds Formation is poorly cemented in the Otter valley to the extent that the rock disintegrates when it is extracted so that only the constituent pebbles and cobbles are used for building. Seventy four of the 343 buildings examined within the area of Figure 2 contain such pebbles and cobbles, of which 54 are walls or embankments.

These statistics emphasise the widespread use of the pebbles for building but their lowly role. Mixtures with other building materials are common, as illustrated in Figure 3. However, carefully selected and graded pebbles are also used to provide an attractive finish to walls (Figure 6) or a decorative coping.

Figure 6. Wall on north side of Salting Hill, Budleigh Salterton, finished with carefully sized “Budleigh Buns” and capped with mud flake conglomerate from the Otter Sandstone.

Chert and Flint

These rock-types are derived ultimately from the Upper Greensand and chalk but because of their very hard and resistant nature, they persist in the superficial deposits and the soil profile of the area of study east of the River Otter and indeed in the river gravels. Both are made mainly of chalcedony, a cryptocrystalline form of silica.

“Chert” is the name applied to such rocks with irregular blocky outlines, grey, brown or orange in colour, and in some cases with enclosed grains of quartz or glauconite defining the bedding of the original sandstone in which the chert masses formed. It is derived mainly from the Upper Greensand.

“Flint” is used here for the nodular form of chalcedony. Building blocks may show the outer skin of the original nodules, white in colour in many cases and showing many re-entrant angles, or may show the conchoidal fracture surfaces typical of the rock type. Flint is more homogeneous than “chert” as used here, and never contains trains of enclosed clastic sand grains. It is derived ultimately from the chalk.

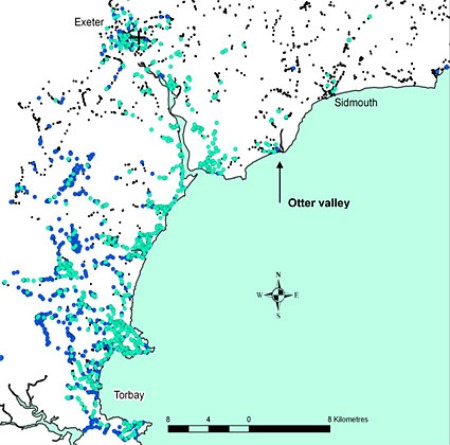

Figure 7. Distribution of flint and chert in buildings in the Otter valley and its surroundings.

Figure 7 shows the distribution of chert and flint in buildings in the lower Otter valley and its surroundings displayed as red and blue symbols respectively. In general, chert from the Upper Greensand greatly preponderates over flint, but in the Otter valley from Newton Poppleford southwards, the opposite is the case and it is largely replaced by flint. Both types of chalcedony occur in Sidmouth buildings. This distribution seems to be related to the occurrence of chert in the Upper Greensand.

Several authors (Gallois, 2004; Jukes-Brown and Hill, 1900, p) have commented on the rapid fall off of chert in the Upper Greensand going westwards so that the upper part of the section completely lacks chert in the cliffs at Kempstone Rocks. West of here, most of the chalcedony in the ground is flint derived ultimately from the chalk, but more directly, from the residual deposits of the Clay with flints derived from its dissolution, and this is reflected in the kind of stone used for building.

Both chert and flint, though extremely durable, are hard to work so they tend to be incorporated in walls as irregular rubble and may be replaced by more easily worked stone for the quoins and dressings of buildings made otherwise mainly of these kinds of stone. Nevertheless, flint is widely used, for example in the outbuildings of Dotton and Passaford Farms, for Pinn farmhouse and April Cottage, Fore Street, Otterton.

A tradition has grown up among builders of the Sid and Otter valleys for the use of flint cobbles for decorative finishes to garden and roadside walling, especially the coping stones of walls. Figure 8 shows one example from Budleigh Salterton. The walls of Flint Cottages in Yettington are also attractively finished with flint cobbles while the wall behind the Jubilee Tap at the junction of High Street with Middletown Lane in East Budleigh is made of this same material (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Garden wall of the Old Vicarage, West Hill, Budleigh Salterton. The panels are finished with flint cobbles with brick surrounds and the footing is of red conglomerate and sandstone from the Otter Sandstone Formation.

Figure 9. Jubilee pump, East Budleigh, composed of carefully graded cobbles of flint. Photo © Mr Tom Gordon.

Imported Grey Limestone mainly from Torbay

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of grey limestone in buildings where it is the main constituent of the walls. A similar distribution is evident when all buildings that incorporate this kind of stone are included except that there are more occurrences in East Budleigh, Bicton and Otterton. The main concentrations of buildings in both cases are in Budleigh Salterton in the south and Newton Poppleford and Harpford in the north.

Figure 10. Regional distribution of buildings containing Devonian limestone from Torbay. Pale blue circles, pale grey limestone; dark blue circles, medium-grey limestone; points, buildings without limestone. See text for full explanation

Figure 10 shows the regional distribution of this kind of limestone of which two types are distinguished:

(i)Pale grey limestone, fine- to medium-grained, with orange, ochre or pink stains and pigmentation, crudely bedded or foliated and with minor silicate impurities.

(ii)Medium grey limestone, similar to the pale grey but more strongly pigmented and in some cases containing well preserved and displayed coral and stromatoporoid fossils.

It is evident from Figure 10 that the main concentration of these kinds of limestone in buildings is around Torbay but that there is an important secondary concentration in Exeter, the Exe estuary and the coast of East Devon. For these localities, the pale grey variety is greatly preponderant and the same applies to buildings in Torbay that are close to the coast.

The explanation is that the limestone from coastal quarries tends to be less strongly pigmented than stone from inland. The limestone used in Exeter, the Exe estuary and the East Devon coastal towns was transported there by ship or barge, mainly in the Nineteenth century and almost exclusively from the coastal quarries (Long Point, Hope’s Nose, Parson’s Hole, Dyer’s, Breakwater and Berry Head Quarries for example), avoiding the much greater cost of transport involved in moving stone on land.

Buildings incorporating these kinds of stone include St Peter’s church, Budleigh Salterton and the vestry of All Saints, East Budleigh as well as numerous walls. Torbay limestone makes an important contribution to the street furniture of speculative late Nineteenth century house developments in Exmouth to the west of the area of study

Not shown in Figure 10 are occurrences of Devonian and Carboniferous limestone from other sources. These mainly occur along the A3052 through Newton Poppleford. They include bedded limestone with black chert bands and nodules from the Westleigh group of quarries near Burlescombe and other grey-coloured and ochre-stained limestones of unknown origin lacking useful distinguishing characteristics.

Cob

Though not a building stone (obviously), cob is a material so characteristic of the area (Figure 11) that it has been included in the study. Cob is a material akin to adobe, composed of soil mixed with straw, water and sometimes other materials (Schofield and Smallcombe, 2007) built up into walls when wet. Many buildings made of cob are finished with render or stucco so its presence must be inferred from architectural aspects of the buildings in which it occurs.

These include very thick walls, batter – walls that get thinner upwards – rather few small openings, bulging and distorted walls and the presence of buttresses to stabilise them, rounded corners and limited wall height, usually one and a half storeys at most, reflecting the limited compression strength of the material (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Cob wall at Place Court, Colaton Raleigh. The cob has an unusual coping of thatch and has been built on a footing of “Budleigh Buns” with narrow brick buttresses for extra stability.

Figure 12. Little Thatch, Harpford

Cob houses figure prominently in the street scenes of Newton Poppleford, East Budleigh and Otterton. Perhaps the most famous of all is Hayes Barton, a substantial house partly of cob and the birthplace of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1552.

There is a noticeable bias in favour of thatched roofs of houses incorporating cob – 72 out of 92 houses identified as having a cob element within the area of Figure 2 are thatched, but it is unclear if this reflects the importance of keeping the rain off the cob walls with deep thatch eaves or is a consequence of listing of the houses concerned by English Heritage (almost one third of the total are listed), preventing the owners from replacing the thatch with something more practical.

Imported quality stone

Higher quality stone has been imported into the Otter Valley from several sources for use mainly in the quoins of buildings and the dressings round doors and windows. Beer Stone is perhaps the most characteristic of East Devon (Figure 13). It is a white fine-grained Cretaceous limestone quarried from Roman times until the Twentieth century at Beer (Scot, & Gray, undated), uniform in appearance and texture and soft when first extracted. It was the stone of choice of medieval masons for church window tracery, well suited to intricate carving because of these characteristics as well as its appearance.

The churches of Venn Ottery and Harpford have it as the main exterior stone used for window tracery and it figures also in the churches at Newton Poppleford, Colaton Raleigh, Otterton and East Budleigh. Beer Stone appears to be the main outside stone of the Rolle mausoleum at Bicton Park although it is not easy to decide which walls belong to the mausoleum and which to the old ruined church.

Figure 13. West door of St Gegory’s, Harpford. White Beer Stone dressings round the door; grey Upper Greensand sandstone quoins and top course of plinth and Otter Sandstone mud flake conglomerate walling.

The main drawback of the stone is the ease with which it is corroded in polluted atmospheres and places where the surface of the stone is flaking off can be seen in all these churches. It is therefore particularly used for interior work not only in East Devon but further afield in the West Country and even in London. Beer stone also turns up in a few other situations. For example the tall roadside wall near Old Hall on the north side of Church Road, Colaton Raleigh contains dressed blocks of Beer Stone, obviously reused, incorporated in a wall of mixed materials including Otter Sandstone, “Budleigh Buns”, Salcombe Stone (see below) and brick.

Beer stone is replaced in the tracery of many churches by Bath Stone, a pale yellow medium-grained Jurassic limestone from Bath and nearby parts of Wiltshire characterised by an oolitic texture consisting of spherical bodies of calcite up to 1mm in diameter set in a matrix of the same material. In some cases it is a repair of older tracery; in others it has been used as part of Nineteenth century building, refurbishment or rebuilding of the church. It is also widely used for the quoins of churches and other high status buildings.

It can be seen in these situations in the parish churches of Newton Poppleford, Otterton and St Peter’s, Budleigh Salterton and also figures in East Budleigh School, Pinn Barton farmhouse and Flint Cottage and No 32 Ottery Street, Otterton and elsewhere. Bath Stone is nationally important and is still quarried. Its use as a repair of or replacement for Beer Stone in preference to Portland Stone (see below) is strange since Portland Stone is arguably a better colour match and comes from less far away.

Upper Greensand Sandstone also figures in the quoins and dressings of houses and churches. It is a brown- or pale grey-weathered sandstone, medium to coarse grained composed of both quartz sand grains and shell fragments in a sparse powdery cement. The brown variety called Salcombe Stone, came from quarries, now closed, at Salcombe Regis, Dunscombe and Branscombe. It is famous as the stone used to face the walls of Exeter Cathedral. The grey variety is quite frequently associated with Beer Stone (see for example Figure 13) and it may be that it was mainly won from Upper Greensand quarries in the Beer area.

Ham Hill Stone, still quarried at Ham Hill near Yeovil, is a biscuit-coloured limestone from the Jurassic, composed of flat fragments of oyster shell in a partly sparry and partly earthy matrix. It is quite coarse grained and the alignment of the shells defines a strong bedding fabric, in many building blocks exhibiting cross-bedding.

Ham Hill Stone is very widely used in Somerset and west Dorset, less so in Devon, but does extend as far west as the Tamar (S. Blaycock, pers.com. 2007) as the quoins and dressings of high status buildings. In the area of Figure 2 it is represented only in the window dressings of St John the Baptist’s, Colaton Raleigh and the quoins and dressings of St Michael’s Otterton.

Portland Stone is the second after Bath Stone of the nationally important building stones used in the lower Otter Valley. It was favoured by Lord Rolle in the Nineteenth century buildings at Bicton. The entrances to Bicton College and Bicton Arena and the Orangery at Bicton Gardens are all of this striking white oolitic limestone but it has not been seen elsewhere in the lower Otter valley.

Other stone used in the Otter Valley

A wide range of other stone is used in the buildings of the valley as a minor component of the walling. The rock-types include Blue Lias limestone probably from south Somerset, soft greenish glauconitic sandstone from the Upper Greensand, more typical of the Sidmouth area, granite of various kinds, purple vesicular lava from the Exeter Volcanic Series, red Heavitree Breccia from Exeter, dark grey dolerite, possibly from the Trusham area, and grey and greenish slate of unknown origin.

Of these, particular attention is drawn to fawn medium-grained sandstone typically with an open texture and lacking shell fragments, and similar sandstone mottled in shades of fawn and red. The mottled variety is used in Woodbury and Littleham and is probably derived from the sandstone beds of the Aylesbeare Mudstone Group (Edmunds and Scrivener, 1999). The fawn variety is quite widespread and it may be that sandstone of several different origins has been lumped together in this category.

It is known that the Dawlish Sandstone, other sandstones from the Exeter Group and the Otter Sandstone can all show a fawn-coloured variant through the reduction of the typical red pigment and its removal in formation water as soluble ferrous salts. However, the occurrence of this kind of sandstone as far away as Bideford indicates that this is very unlikely to be the only origin. It has been suggested that some examples of the stone are imported from Yorkshire but the informant could not remember the name of the quarry.

Finally, an unusual chert breccia is locally quite plentiful as a minor constituent of walls (Figure 14). It is derived from the Clay with Flints by secondary cementation of the chert and flint fragments. The same material is used for the Shell House and grotto in front of it at Bicton Gardens and forms the sarsen stones well known, for example, at Staple Fitzpaine in south Somerset, the Nine Stones stone circle at Winterbourne Abbas near Dorchester and used at Stonehenge. A notice in the Bicton Shell House states that the stone was taken from the cliff top between Sidmouth and Beer.

Figure 14, Chert breccia boulder in the footings of the nave, south side of Harpford church. Angular fragments of yellow chert set in a hard chalcedony matrix.

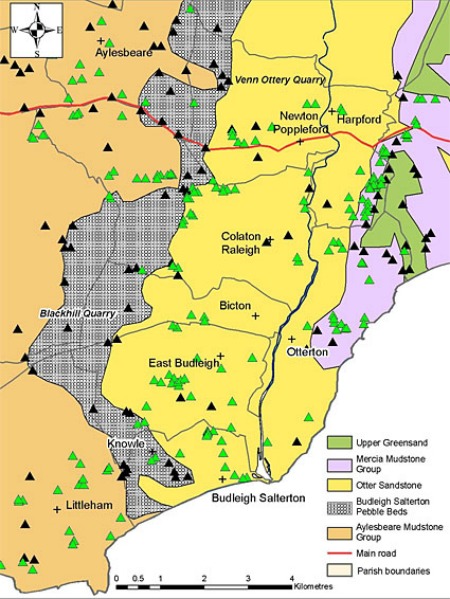

Sources of Stone

Figure 15 shows the localities of pits, quarries and related landscape features mainly identified from the literature, against a background of the outline geology. The green symbols correspond to the names of fields on the tithe maps that may indicate the extraction of rock in the past, where there is no corroboration from other sources. The black symbols indicate the sites of pits or quarries from a range of other sources including the geological literature, especially the early memoirs of the British Geological Survey and the Ordnance Survey 6” maps, 1st Edition of the late nineteenth Century, corroborated in some cases by suitable field names on the tithe maps and in a surprising number of cases, considering the age of the primary sources, still visible on the ground, in the air photos of Google Maps or marked by quarry or pit symbols on current Ordnance Survey mapping.

Figure 15. Location of pits and quarries and related landscape features overlaid on outline geology. Green triangles, tithe map field name only; black triangles, other sources. See text for full explanation.

The tithe map data is for the most part hard to evaluate. In a minority of cases, there is a clear indication of the former existence of a pit or quarry as in the occurrence of names like Pit Close or Quarry Field. Pits in operation at the time of the tithe apportionment usually have a land use called “waste”. Conversely, pits and quarries that were no longer in operation have in many cases been converted to orchard and the field surrounding such former quarries may be called names like Pit Orchard.

It is often the case that a group of adjacent fields have names related to the extraction of stone, or some other commodity in which case, the former presence of a pit or series of them may be inferred with some confidence. This is so particularly where the adjacent fields had different owners at the time of the apportionment and appear in widely different parts of the apportionment record.

However, it is probable that many of the field names represented by green triangles in Figure 15 are unrelated to mineral extraction. The term “marles” appear in many cases on the Otter Sandstone outcrop as well as the Mercia and Aylesbeare Mudstones. In modern usage it refers to a calcareous mudstone and would be a suitable term to describe the soil derived from the last two rock groups but seems less suitable for the Otter Sandstone, so perhaps it formerly meant something slightly different. In any case, it is unlikely that pits and quarries located on the mudstone formations were sources of building stone. It was the practice to apply marl to land with acid soil (marling) and this is a much more likely use for the pits located in the mudstone formations.

It has also not been possible to establish a link through the literature between any particular building made of local stone in the lower Otter valley and the pit or quarry from which the stone was won. In the case of chert, flint and “Budleigh Buns” there are numerous pits shown on Figure 15 on the outcrop of their source formations which could have been sources of building stone.

However, these materials are very persistent in the soil and it is perhaps more likely that they were just collected from near the building site, or in suitable cases off the beach, rather than being brought from further away. Ford (2002, p63) mentions the collecting of flints from the fields for use as building material.

With regard to the Otter Sandstone, Ford (2002) also mentions the winning of it for building from small quarries scattered across the outcrop. The churchwardens of East Budleigh Hundred record the winning of building stone from the sea cliffs east of the mouth of the Otter and its transport by boat to a landing place called Bankley (Brushfield, 1894), now identified at the junction of the Otter with the Budleigh Brook near Pulhayes Farm (D. Daniel, pers. comm. 2011).

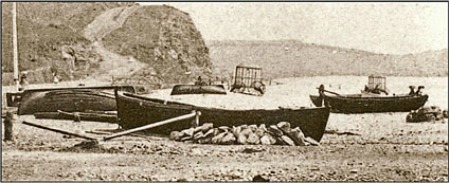

Finally, there is a fine early photo showing boats drawn up on the shingle on Salterton beach at the mouth of the Otter with the stone they have just brought there (Figure 16), showing that the tradition of bringing stone by sea continued into the Nineteenth century.

Figure 16. Boats lying on Salterton beach with their cargo of stone beside them.

Researched and written by Michael Barr © 2011.

References

Barr, M.W.C., 2006. Building with stone in East Devon and adjacent parts of Dorset and Somerset. Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science, 138, 185-224.

Barr, M.W.C., 2007. Building stone at the western edge of the Blackdown Hills. Geoscience in south-west England, 11, 348-354.

Brushfield, T.N., 1894. The churchwardens' accounts of East Budleigh. Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association for the Advancement of Science, 26, 335-400.

Edmunds, R.A. and Scrivener, R.G., 1999. Geology of the country around Exeter. Memoir of the British Geological Survey Sheet 325 (England and Wales). HMSO.

Ford, A., 2002. Mark Rolle: His Architectural Legacy in the Lower Otter Valley. The Otter Valley Association, 88pp.

Gallois, R.W., 2004. The stratigraphy of the Upper Greensand (Cretaceous) of south-west England. Geoscience in south-west England, 11, 21-29.

Gallois, R.W., 2009. The origin of Clay-with-flints: the missing link. Geoscience in south -west England, 12, 153-161.

Jukes-Brown A.J. and Hill, W., 1900. The Cretaceous Rocks of Britain I: The Gault and Upper Greensand of England. Memoir of the geological Survey of the UK. HMSO.

Schofield, J and Smallcombe, J., 2007. Cob Buildings: a practical guide. Black Dog Press, Crediton.

Scot, J. & Gray, G., undated. Out of the Darkness, a Brief History and Description of the Old Quarry, Beer.

131 BS-G-00014 any